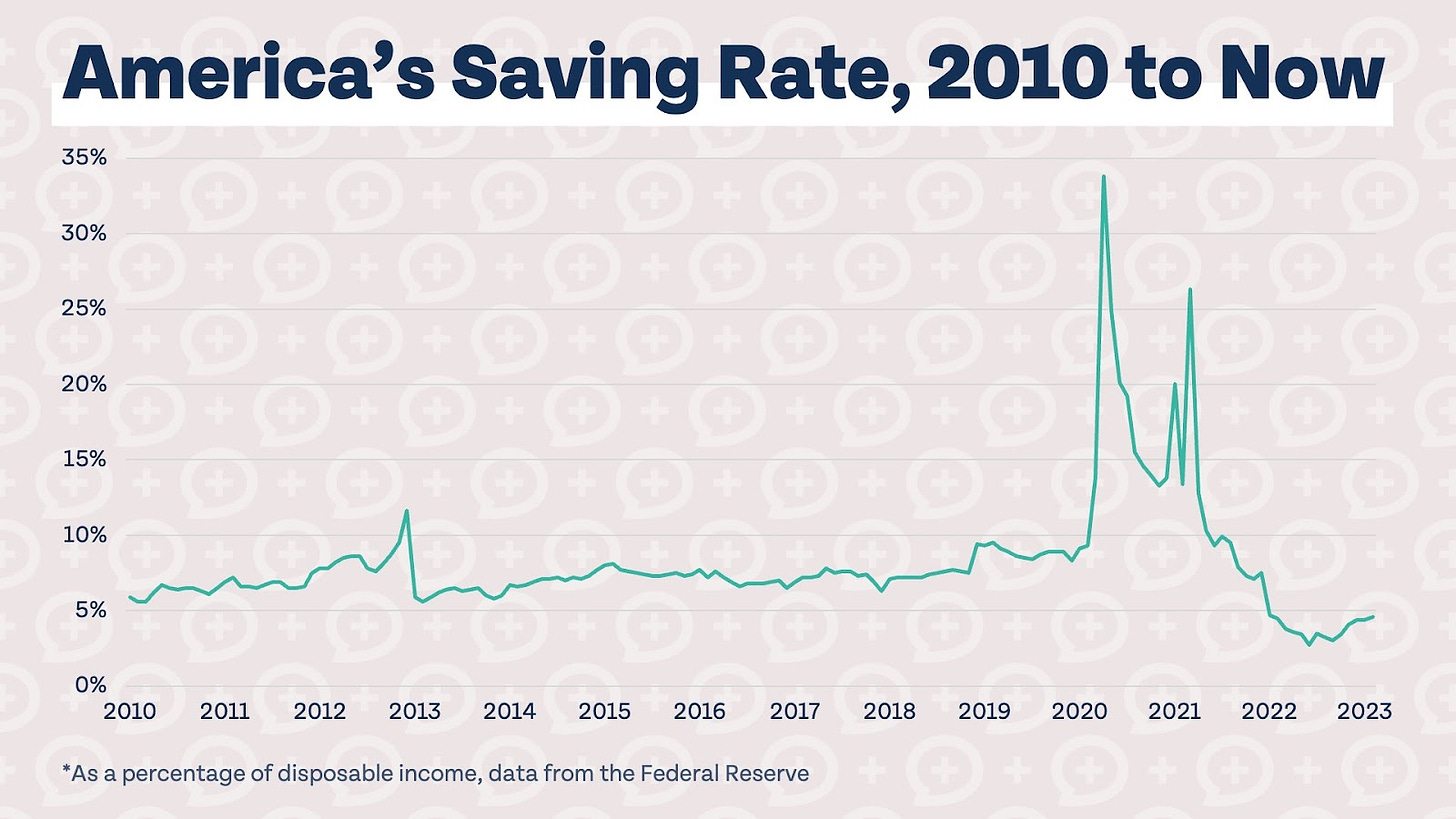

Americans aren’t very good at saving money. During the pandemic, when we were stuck at home and received stimulus checks, the savings rate in the country reached nearly 35%. Now we are saving less than 5%, measured as a percentage of disposable income. If you measure savings rate as a percentage of GDP, which is a more accurate reflection of how much we are truly saving, we’re putting away less than 2% of our money for the future.

Why are we so bad at saving money?

We’ve been bad at saving money for a long time, as you can see from the chart above. But something unique happened in 2020 – many Americans received unexpected money, but that doesn’t explain why they didn’t spend it. We know that families in the top 10% of net worth in America carry credit card debts of $12,890, on average. The majority of Americans making over $100,000 describe themselves as living paycheck-to-paycheck, and 16% have trouble paying their bills in a given month.

Money doesn’t change the financial psychology and behavior of Americans, so how and why did we save so much during the pandemic?

Present bias

A study published several years ago by the National Bureau of Economic Research found two primary reasons why Americans are so bad at saving money. These two underlying reasons remained even after controlling for financial literacy, income, age, educational attainment, and more. The first factor that makes us bad savers is what’s known as a present bias: we value what money can do for us now more than what it can do for us in the future.

Our present bias explains why we were so good at saving money during the pandemic. Clearly our discipline didn’t improve and our behavior wasn’t changed, as Americans have returned to saving even less than we did before the pandemic. During the pandemic it seemed like a better deal to save money for the future than to spend it while we were stuck indoors with not much to do. We were not able to go to concerts, sporting events, movie theaters, or even out to dinner. The goods that we could use from home, like popular electronics, home workout gear, and even board games and puzzles, became difficult to find.

Our present bias was overcome because the present we were living in was not that great, to put it mildly. We knew that better days were ahead, days where we would be able to take vacations and resume our normal day-to-day activities. So we saved more money than we ever have since the Federal Reserve began tracking our savings rate all the way back in the 1950s.

While Americans overall went back to saving just as little as they ever have, you don’t need another pandemic to overcome your present bias – but you do need to understand the magic of compounding interest.

Exponential growth bias

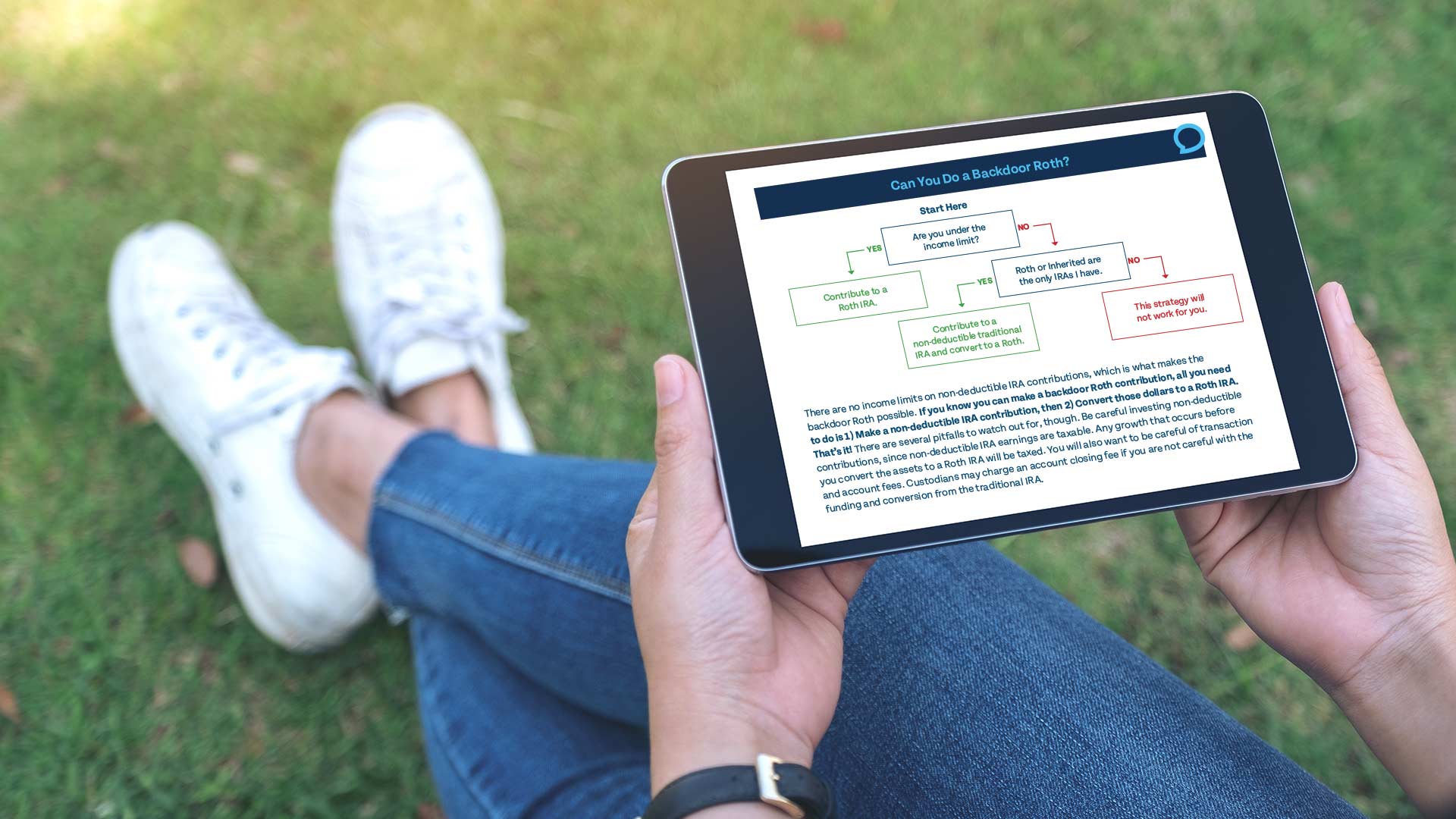

The second factor researchers identified as responsible for a lack of saving is a bias against exponential growth. In other words, we just don’t understand it. Our lack of understanding has nothing to do with intelligence or education, our minds are just wired to think linearly instead of exponentially. The Financial Order of Operations has been so popular and resonates with so many folks because it is linear and easy to understand. You start on Step 1 and go in order until you reach Step 9. Sometimes you are forced to move backwards, but it is a linear process.

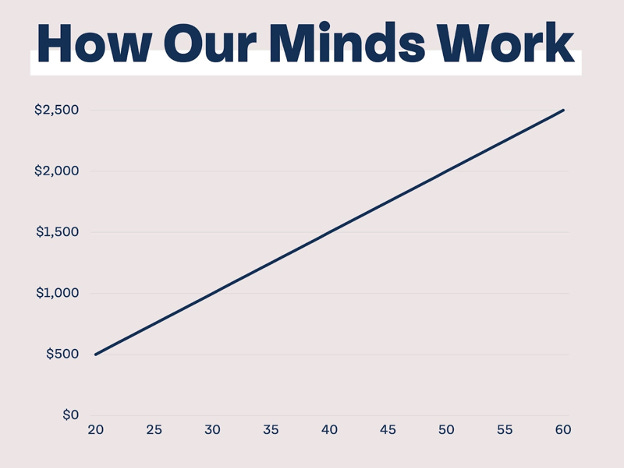

Here’s an example of how our minds work when we think about money growing.

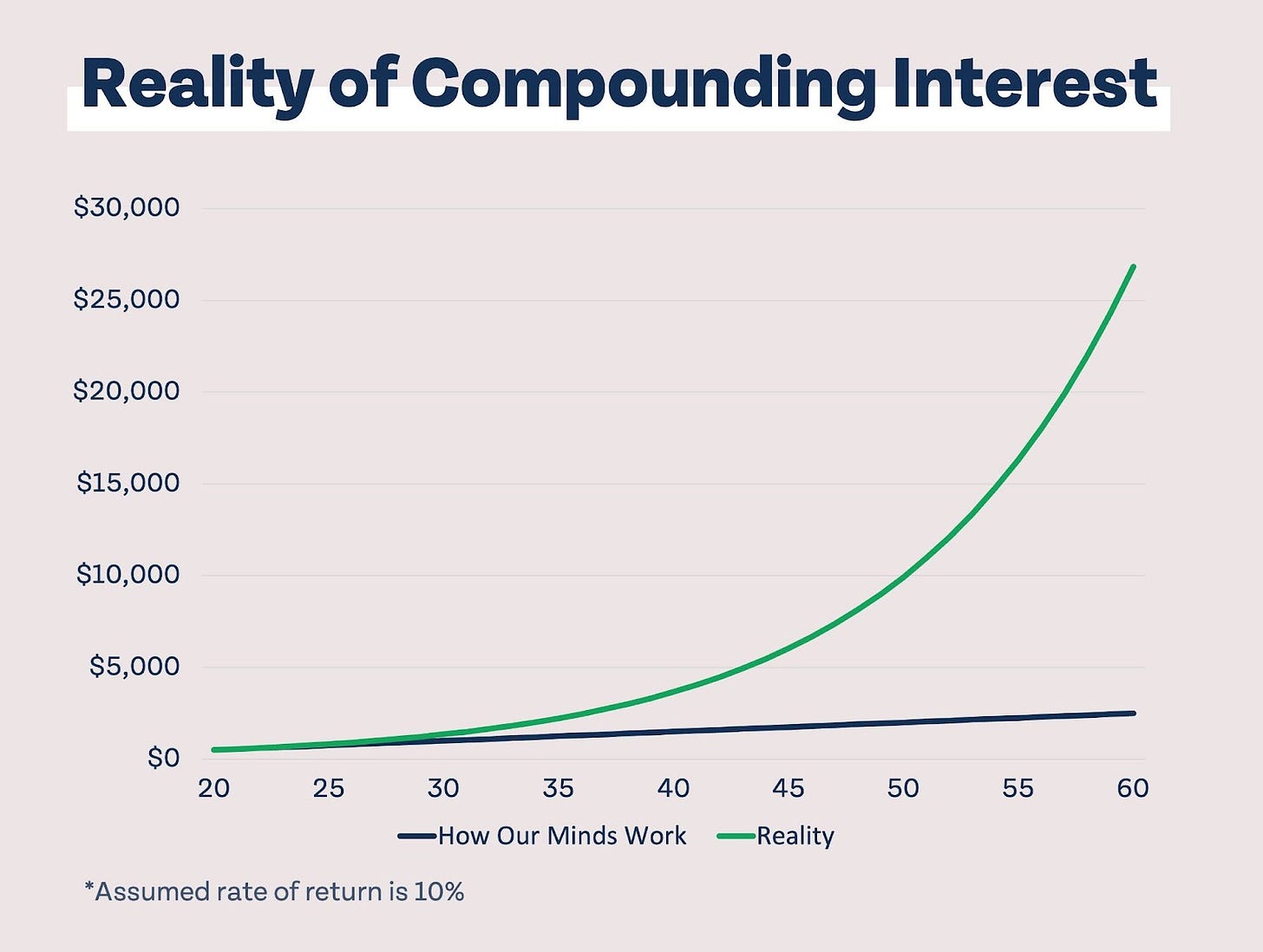

If we invest $500 at age 20 for retirement, it will grow steadily through time. By age 60, we’ll have 5x the amount we started with! When many people consider saving for retirement, they are assuming – perhaps subconsciously without even recognizing it – that their money will grow steadily each year. The reality is quite different.

The magic of compounding growth looks much different than linear growth. We end up with over 50x the original $500 investment, with an assumed return of 10% annually. Linear growth doesn’t look much different from compounding growth at first; throughout the 20s and into the 30s, the lines look pretty similar. Compounding interest takes decades to really start shining.

How do you overcome the bias against compounding growth? It can be difficult. Even if you know your money will eventually grow exponentially, it’s not easy to diligently save and invest without seeing exactly what those dollars will become. In the present, you know what your money could become – a new phone, a vacation, or a new car. Future dollars are more nebulous.

If you haven’t been investing for decades and seen the magic of compounding interest for yourself, try talking to a close friend or older family member and take a look at how their accounts have grown. Or even better, see what your money could become based on historical returns of the market. Since 1980, the S&P 500 has annualized 11.56%. 43 years is more or less an average working career; if someone invested just $500 per month since 1980, they would have over $7 million today. If they were able to invest $1,000 per month, they would now have over $14 million.

We are naturally biased towards gratification now and have a hard time understanding compounding interest. However, those biases can be overcome by seeing how compounding interest works and watching it in action in our own retirement accounts. The researchers estimated that eliminating those two biases alone could increase our retirement savings by as much as 70%. There is no better place to be to learn about deferred gratification and compounding interest than The Money Guy Show!