Matt’s question is up next. Is that Matt or Max? Matt.

Matt, one T or two T’s?

I knew you were asking. I knew it before it even came. I knew he was asking that question.

It’s with two T’s, same as our Matt’s spelling.

Could you explain the downsides of having too much money in your Roth bucket, like Roth 401(k) or Roth IRA? Or is there a downside? I’m interested to see what you say.

Can you tell me what’s wrong with being too wealthy? What happens if I have too much money, right?

Okay, I’ll try to approach this.

Realistically, there probably aren’t a ton of downsides to having too much money in the Roth bucket. We talk about the three buckets we want you to have: the tax-free bucket (that’s Roth and HSAs), the tax-deferred bucket (that’s your 401(k)s), and your after-tax bucket (your brokerage accounts). Generally, we like to say we want you to have money in your after-tax bucket because, realistically, you aren’t supposed to be able to get to your Roth assets until after age 59 and a half.

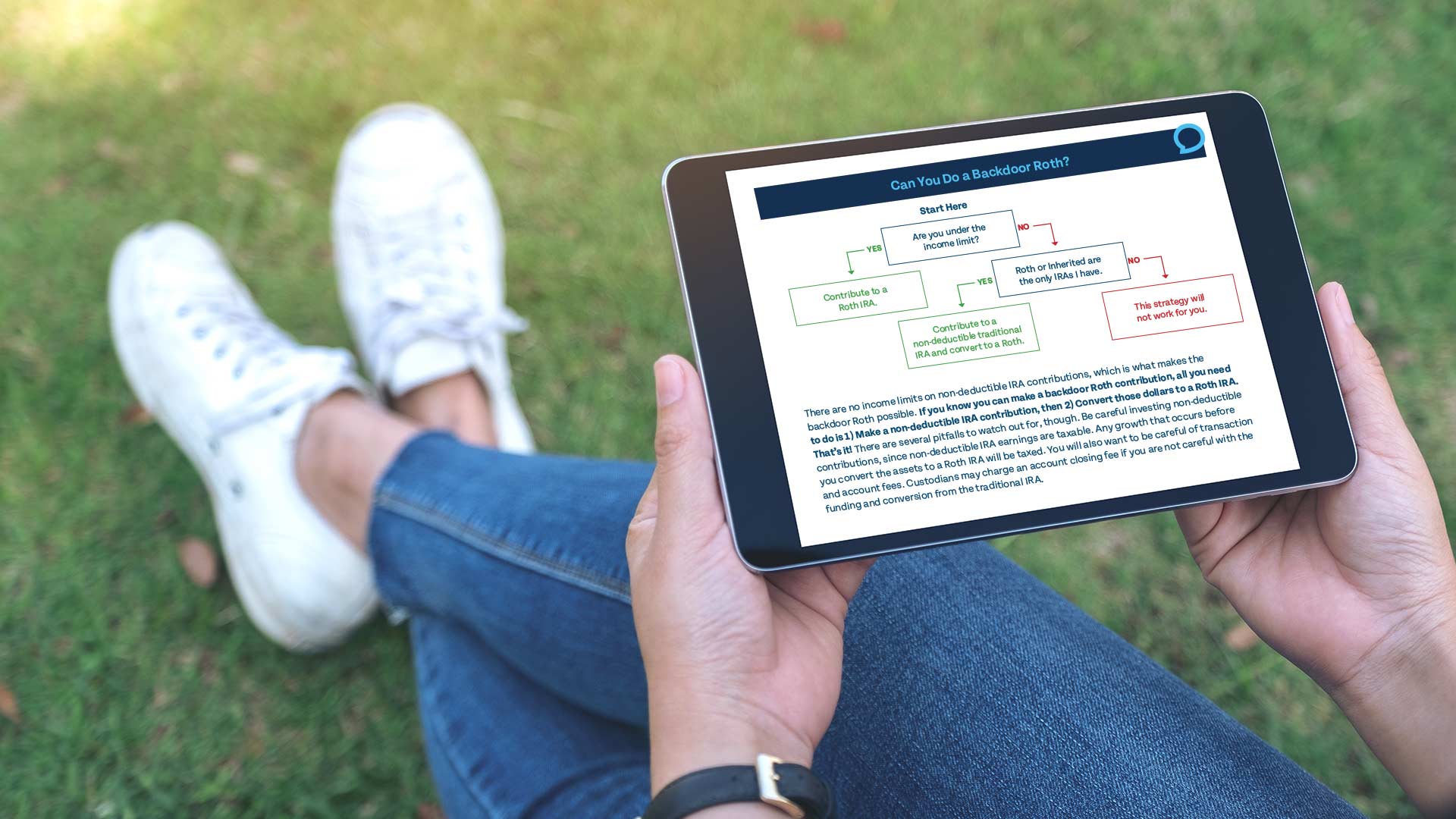

But you guys are financial mutants out there, and you recognize that there is a little break glass in case of emergency clause when it comes to Roth IRAs, allowing you to get to your Roth basis earlier than 59 and a half. Basis meaning the money you’ve put into the Roth. If you have a large enough pot of money that it’s all in Roth, I’m going to use a ridiculous number: say you have $10 million in a Roth IRA. Is there going to be a downside to having that as opposed to having $10 million in a 401(k) or an after-tax brokerage account? Maybe not, assuming the basis is large enough to bridge the gap from when you need the resources until you reach 59 and a half. You have to make sure the contributions are large enough to satisfy that.

But absent that, I’m having a hard time thinking of another downside.

I’ll put the low-hanging fruit out there: there’s a little bit of a hassle factor. Getting to your Roth money requires taking a distribution, some paperwork, so we’ll say there’s a little bit of a hassle factor. However, the real struggle with Roth money: you emotionally get so connected with your Roth money because you recognize that the government restricts how much you can put in every year. What you can make—if you make too much money, they don’t even want you funding these things because it’s a true great benefit.

When I talk about the wealth multiplier and how that dollar has the potential to become $88 for a 20-year-old, and then you think about that, well, 87 of those dollars are strictly from growth—how cool would it be if they’re tax-free? And you do this thousands of times over. You can quickly see how emotionally you’ll be like, “I love…” It becomes your precious. I love my Roth assets.

So, there’s not really a problem with having too much Roth money. I guess if you get too much, the government might start wondering if they should change all the rules for everybody else just because one billionaire did something creative. Let’s not go down that rabbit hole, but no.

But it’s true. That’s the only negative thing I can say, because otherwise, it’s more of the emotional struggles you’ll have. People load up their Roths, and even when you get to financial independence, usually you want to keep your Roths even as you get older because they’re great legacy and estate planning tools. You can pass them on and let your heirs have those 10 years to continue to grow in a very tax-favored way.

So, Matt, if it’s a trick question and you’re trying to trip us up, I’ll give you the low-lying fruit of hassle factor and easy access to cash because you don’t want to be using this as your emergency resource. But other than that, we absolutely love Roth money. It’s one of the first accounts you’re going to fill up when you start investing, and it’s going to likely be one of the last accounts you ever take money out of—if you ever take money out of it, because you might just pass it down to your loved ones later.

I want to hit the commenters. I want to head them off at the pass because what I can hear is the next line of thinking, and this is going to riddle all through the comments: “All right, well, if Roth is that great, why don’t I put everything in Roth right now? Why don’t I try to get my Roth bucket as big as possible now?” I think if that was where you were going with your question, Matt, there are merits to contributing to other accounts instead of Roth.

Specifically, if you are in a higher tax bracket right now and can do pre-tax contributions or tax-deductible contributions to some type of retirement account, you’re going to have substantial tax savings. If you’re going to be in a lower tax bracket later in life, in retirement, you’d rather get the tax savings now and pay the tax later. There’s an arbitrage that you can take advantage of there.

Just because we’re saying there are no downsides if you end up with a bunch of money in Roth, that’s not to say there aren’t downsides that ought to be considered when it comes to deciding to contribute to either pre-tax or Roth. But to do that, you have to have a very high income tax currently, and it could be sweetened with or soured by a higher state income tax.

If you’re a high-income person, let’s just say California—not trying to pick on California, it’s just one that comes to mind easily—you have a 37% federal tax rate if you’re in the high-income bracket and a 13.3% state income tax. You can quickly realize we’re at 50%. So it’s things like that that might make you say, “Well, I know when I retire, I’m potentially going to move to a state that has zero income tax, plus I’m going to have a much lower tax rate in retirement.” Now there’s that arbitrage situation, especially if you retire pre-75.

Maybe while you’re in those lower income years, you might still try to convert some of that money to Roth. So it’s not that the strategy is against Roth, you’re just changing the timing to maximize the tax planning opportunity.

Love it!