Change your life by

managing your money better.

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter by entering your email address below.

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter by entering your email address below.

You guys know what? I’m actually excited about debt.

Now wait—hear me out.

There’s a wide spectrum of how people in America treat debt:

On one end, you have the debt crusaders—people who swear off any kind of debt, believing that borrowing money is the worst thing you can do. For them, the only path to wealth is complete debt freedom.

On the other end, you have folks who are way too comfortable with debt—financing everything from vacations to luxury cars, carrying credit card balances, and driving around in vehicles with payments that eat up their income.

But what if I told you there’s a middle ground?

Yes, debt is dangerous, but it can also be a tool for improving your financial life.

To treat debt wisely, we need to distinguish between high-interest debt and low-interest debt. Two key factors determine this:

Your age

The type of debt

Why these matter:

Younger individuals have more time to let investments grow, which increases the potential for higher long-term returns.

Not all debt is equal—some is riskier and more costly than others.

In our Financial Order of Operations (FOO), we separate high-interest debt from low-interest debt:

High-interest debt is tackled early, even before most investing.

Low-interest debt is addressed later because it may actually work in your favor.

Arbitrage means taking advantage of a difference between two rates.

Example:

If your credit card has a 20% interest rate, and you’re earning only 10% on investments, you’re losing 10% each year.

But if you have a 4% mortgage and can earn 10% investing, you’re gaining a 6% advantage. That’s positive arbitrage.

To evaluate whether to pay off debt or invest, you need to know:

Risk-free rate of return: What you earn from essentially zero-risk investments (like U.S. Treasury bonds—currently about 4%).

Risk premium: The extra return expected for taking on risk (e.g., the stock market, with a historic 10% return, gives a 6% premium over Treasuries).

Rule of Thumb:

If your debt interest rate is higher than your expected investment return (risk-free rate + risk premium), pay off the debt.

If it’s lower, investing may be better.

Let’s break down major types of debt using this framework.

Always considered high-interest.

Average interest rates are around 20% or higher.

Hidden fees and penalties make them extremely dangerous—we call this “chainsaw dangerous.”

A 10% investment return can’t outpace a 20% credit card rate.

💡 Eliminate credit card debt ASAP. It’s a financial emergency.

Trickier, because cars depreciate fast:

Lose 10% immediately after purchase.

Lose 60% in value within 5 years.

While cars are necessary, financing them at a high interest rate is often a losing game.

Ideal Rule:

The 23/8 rule:

Put 20% down

Finance no more than 3 years

Monthly payment should be <8% of gross income

High-Interest Threshold by Age:

20s: >10% interest = high

30s: >9%

40s: >8%

50+: Any car loan should be considered high-interest

No depreciation, but still must be handled wisely.

The “First-Year Financing Rule”:

Your total student loan debt should not exceed your first-year salary.

High-Interest Threshold by Age:

20s: >6% interest

30s: >5%

40s: >4%

50+: Ideally no student loan debt

Most controversial, since it’s often the largest purchase you’ll make.

Many people like paying off mortgages early for peace of mind—and that’s fine—but…

We usually consider mortgages as low-interest debt. Here’s why:

Houses appreciate (around 3.8% annually in the U.S.)

Interest is fixed, and refinancing is possible down the road

Paying extra early may reduce investing potential

Illustration:

$300,000 mortgage at 7% for 30 years = $1,995/month

Add $500/month = mortgage paid in 17 years, then invest for 13 years → grows to ~$800,000

But investing the $500/month from the beginning over 30 years = over $1.1 million

➡️ Don’t lose compounding power by focusing only on mortgage payoff.

Understanding your age, the type of debt, and your financial goals allows for a more strategic plan—not just blanket advice like “all debt is bad.”

By following the Financial Order of Operations (FOO), you can:

Pay off the right debts first

Maximize wealth-building potential

Put your money to work—for you, not against you

Subscribe on these platforms or wherever you listen to podcasts! Turn on notifications to keep up with our new content, including:

You guys know what I am so excited about? Debt. Now wait, hear me out. There’s a broad spectrum of how people in America treat debt. On one hand, you have the debt crusaders—the people who swear off any kind of debt, avoiding loans at all costs. They believe borrowing money is the worst thing you can do and the only way to build wealth is to live completely debt-free. On the other hand, you have those who are way too comfortable with debt, financing everything from vacations to luxury cars, carrying credit card balances month over month, and driving around their wealth in that hefty car payment eating up their income.

But what if I told you there was another way—that debt, yes, is dangerous, but it can also be a tool to help you create a better financial life for yourself? You know something else that can help you create a better financial life? Hitting that like button—show it some love if you haven’t done that already.

All right, since we treat different debts differently, we need to really define what counts as high-interest debt versus low-interest debt. And the real answer to whether a debt, broadly speaking, is high or low interest depends on two major factors. The first factor is your age, and the second is the type of debt you have. These two things make all the difference, because the younger you are, the more time you have for your investments to grow. That means you can more reasonably expect a higher long-term return on your investments.

And not all debt is created equal. Some debts are far more dangerous than others and they need to be tackled immediately, while others might actually be working in your favor. This is exactly why in the old reliable Financial Order of Operations—or what we like to call the FOO—we separate high-interest debt from low-interest debt, putting high-interest debt early in the process, even before most investing, while low-interest debt is literally the last step. And there’s a very important reason why: something called arbitrage.

Let’s take credit card debt for example. If your credit card has a 20% interest rate, even if you’re investing and earning like 10% per year, you’re still losing money overall. That’s a 10% loss annually—10% investment return minus a 20% interest cost. On the other hand, if you have a 4% mortgage and you can reasonably earn 10% on your investments, that’s a 6% positive gap in your favor. That right there is arbitrage—and you can see how it can work both for or against you.

So when evaluating the arbitrage opportunity of a given debt and determining whether it would make more sense to pay it off or more sense to invest, we need to understand two additional concepts. And those are: one, the risk-free rate of return, and two, the risk premium.

The risk-free rate of return is what you could earn on investments with essentially zero risk—like true U.S. Treasury bonds. Right now, that’s about 4%. The risk premium is the extra return you expect from taking on risk, like investing in the stock market. For example, the S&P 500 has returned about 10% per year historically, meaning that the risk premium is about 6%—that’s 10% market return minus the 4% risk-free rate.

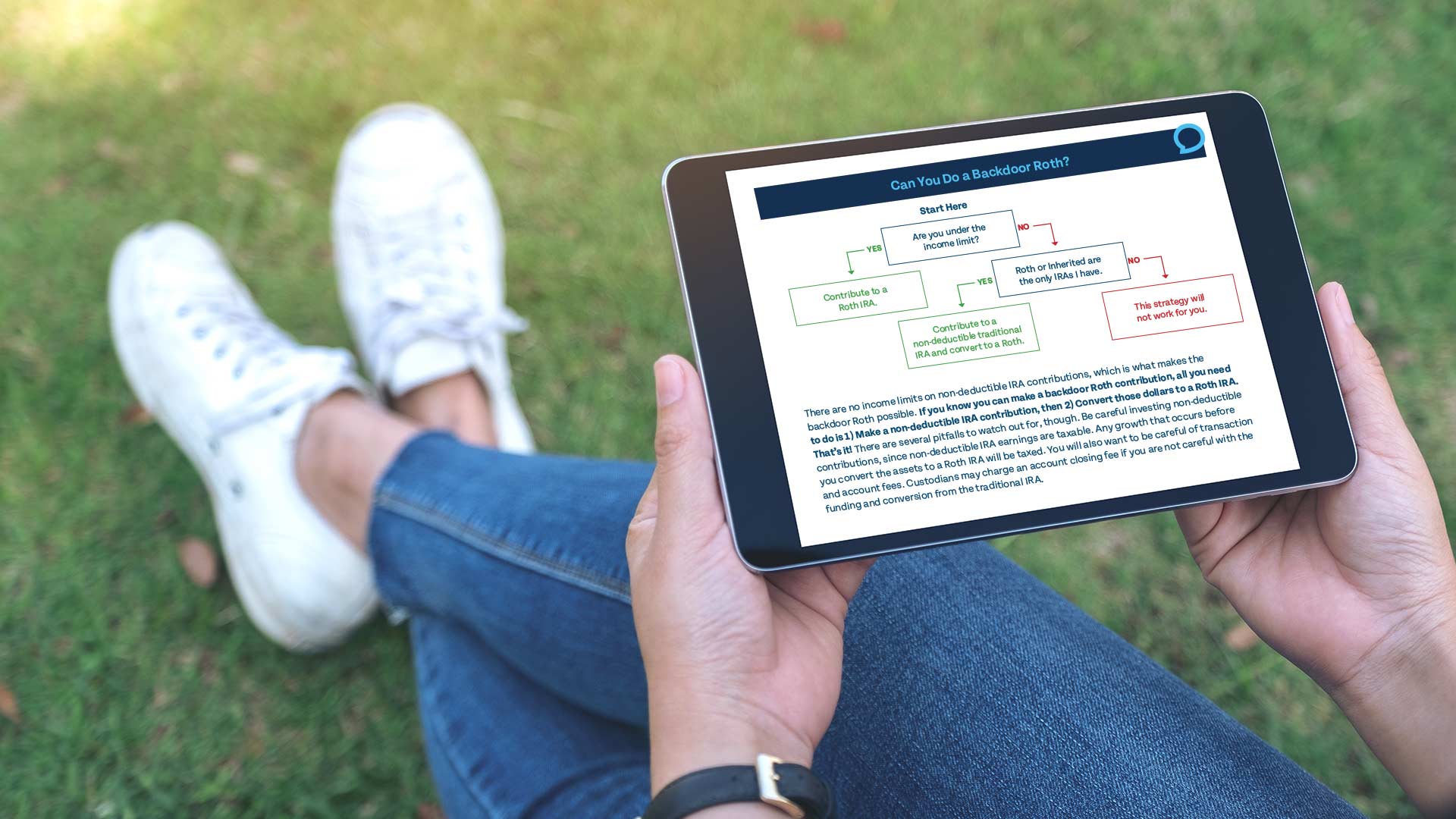

So how do you use this? Well, it’s pretty simple. If the interest rate on your debt is higher than what you could reasonably expect to earn investing—which is the risk-free rate plus the risk premium—you should pay off the debt ASAP. But if your debt interest rate is lower, investing might be the better option because it presents a positive opportunity for arbitrage.

But while the risk-free rate plus the risk premium rule of thumb is a great starting point for evaluating debt, not all debt is the same, and not everyone is in the same financial situation. That’s why we developed a few more nuanced rules to help you evaluate whether you might want to consider debt as high-interest or not. So let’s walk through the different types of debt and how we apply this framework. We’re going to talk through credit cards, automobiles, student loans, and mortgages—what counts as high-interest for each, and some other rules we have to ensure you’re taking on debt responsibly.

All right, first let’s talk about the big one: credit cards. We always, always count them as high-interest, and they are almost always a bad arbitrage bet. Credit card debt is the worst kind of debt because it has interest rates of like 20% or greater. Not only that, they often have hidden fees and penalties that could cause payments to spiral out of control. We call it chainsaw dangerous. Even the basic litmus test of using the risk-free rate plus the risk premium rule—a 10% stock market return—can’t come anywhere close to outpacing a 20% interest rate on your credit card. This is why in the FOO, credit card debt gets prioritized ahead of nearly everything else. It is quite literally a financial emergency that needs to be eliminated ASAP.

Well, well, if it isn’t our old friend—car loans. Car loans are a little bit trickier because cars lose value immediately. A brand-new car loses 10% the moment you drive it off the lot and 60% within the first 5 years of ownership. So you have to evaluate the interest rate with that in mind. And while we can all agree that cars have utility, if you’re financing a car at too high of an interest rate, it’s going to be a losing battle.

Now don’t mishear me—we would always prefer you pay cash for cars. But for a lot of folks, that’s just not possible. And in addition to the interest rates, we have a rule called the 20/3/8 rule to help keep debt manageable: you put at least 20% down, you can’t finance for any more than 3 years or 36 months, and the monthly payment cannot be greater than 8% of your gross income.

But when it comes to what we want to count as high-interest debt for your cars, if you’re in your 20s, anything that’s over 10% is probably high-interest. In your 30s, anything over 9% is probably high-interest. In your 40s, anything over 8%. And beyond 50, we’d say any car loan should probably be treated as high-interest debt.

All right, all right—that’s cars. Now let’s talk about student loans. Depreciation is obviously not a concern like it is with cars, but we still want to ensure you’re taking on a reasonable amount of debt. That’s why we came up with the First-Year Financing Rule, which states that your total student loan debt should not exceed what you expect your first-year salary to be when you’re looking to pay them off.

And when it comes to evaluating the debt, the high-interest debt threshold for student loans—like cars—depends on your age. If you’re in your 20s, any student loan with an interest rate above 6% is probably high-interest. By your 30s, the threshold lowers to 5%, and by your 40s it drops even further to 4%. And from age 50 onward, we really don’t want you carrying any more student loans.

The last one is mortgages, and this one probably has the most discourse surrounding it because for many, it’s literally the biggest asset you will ever purchase. And rates have been high for a few years now—this gets people wondering if they should now think of mortgage interest rates as high-interest debt.

Some people swear by paying off their mortgage early because it gives them peace of mind—and there is certainly some value to that. But here’s the thing: we would pretty much always consider mortgages to be low-interest debt, and let me explain why.

First, it’s generally safe to assume that over the long term of a mortgage—like for example 30 years—a home is going to appreciate in value. It’s an appreciating asset. The average appreciation for homes in the United States is around 3.8% per year. And just like you would with the depreciating asset like a car, you have to bake in the appreciation of your home when you think about the interest rate.

And perhaps more importantly, the interest rate is fixed—it’s not forever. Refinancing can be your friend. So what we don’t want is for you to pay a ton extra on your mortgage just to refinance later to a much lower rate, because then it feels like those dollars could have been better put to work somewhere else in your army of dollar bills.

Now that you’re at a lower rate, if you’re putting extra toward your mortgage, that leaves less margin in your budget for saving and investing. For example, let’s say you have a 30-year, $300,000 mortgage at 7% with a monthly payment of $1,995 and an extra $500 you’re trying to figure out what to do with. You could pay that extra $500 towards the mortgage, and that would allow you to pay it off in 17 years as opposed to 30. After which, then you could invest the freed-up $1,995 plus the $500 for the remaining 13 years.

Now if we assume a 10% rate of return, that strategy would grow to about $800,000. However, if instead you would have invested that $500 per month from the very beginning, instead of prepaying your mortgage, while continuing to only make the minimum mortgage payments, your investments would compound over the full 30-year period, resulting in a portfolio worth over $1.1 million by the time the mortgage is paid off. The second approach dramatically increases long-term wealth due to the power of compounding, and we don’t want you to miss out on that just to pay down a mortgage faster.

By accounting for your age, the type of debt, and the variables surrounding it, you’re much more able to come up with a personalized plan of attack that makes the most of your dollars and gets them working for you—rather than just saying, “All debt’s bad debt.” By following the FOO, you can make more strategic financial decisions, ensuring that you’re paying off the right debts first and maximizing your wealth-building potential.

Financial Order of Operations®: Maximize Your Army of Dollar Bills!

Here are the 9 steps you’ve been waiting for Building wealth is simple when you know what to do and…

View Resource

How about more sense and more money?

Check for blindspots and shift into the financial fast-lane. Join a community of like minded Financial Mutants as we accelerate our wealth building process and have fun while doing it.

It's like finding some change in the couch cushions.

Watch or listen every week to learn and apply financial strategies to grow your wealth and live your best life.

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter by entering your email address below.