Series I savings bonds were first issued by the U.S. Treasury in September of 1998, but have flown under the radar until recently. I bonds were designed to offer Americans a way to protect the purchasing power of their money in a safe investment backed by the U.S. government. The bonds aim not only to keep up with inflation, but offer a return slightly above the rate of inflation.

How do I bonds work?

To offer a return above and beyond inflation, the interest on I bonds has two components: a fixed rate and an inflation rate. The fixed rate paid never changes over the entire 30-year life of the bond. The inflation rate is adjusted every six months, in May and November, based on non-seasonally adjusted CPI-U. However, the interest rate changes don’t go into effect for all I bonds at the same time; if you bought an I bond now, in January, the rate will not change in May but in July (six months from the date of issue), and every six months going forward.

This means if you expect rising interest rates, it is better to purchase I bonds right after new interest rates go into effect in May and November rather than before. That way, you get rate increases right after they are set and don’t lock in lower rates. If you expect falling interest rates, it is better to purchase I bonds right before new interest rates are announced (instead of after) so you lock in higher rates for six months. If you plan on holding I bonds long-term it doesn’t matter when you buy them, because you’ll receive the same interest rates, although you might get them six months sooner or later than others.

I bonds can be purchased at any time online from TreasuryDirect. Paper I bonds can only be purchased with your tax refund. You can purchase up to $10,000 per year electronically, and an additional $5,000 per year through tax refunds. This is per Social Security number, so an individual can purchase a total of $15,000 per year and a married couple would be able to purchase $30,000 in a calendar year. Interest may be claimed annually or can be deferred until redemption, maturity, or other taxable disposition, and interest is exempt from state and local income tax (but subject to federal income tax). I bonds mature 30 years from the date of issue; they can be redeemed as soon as 12 months from the date of issue, but you’ll have to give the last three months of interest back. After five years, there is no penalty.

Why weren’t I bonds popular investments?

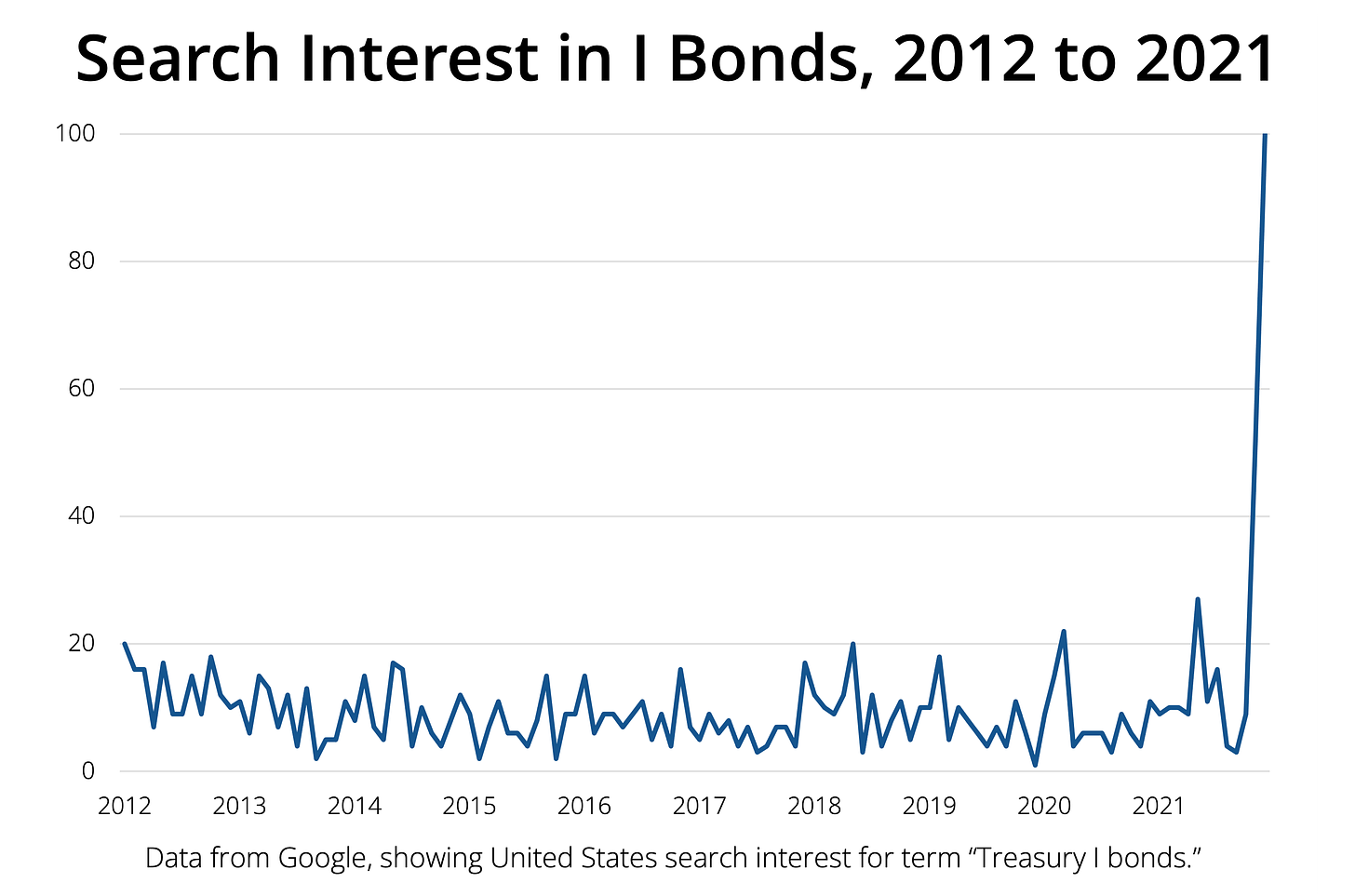

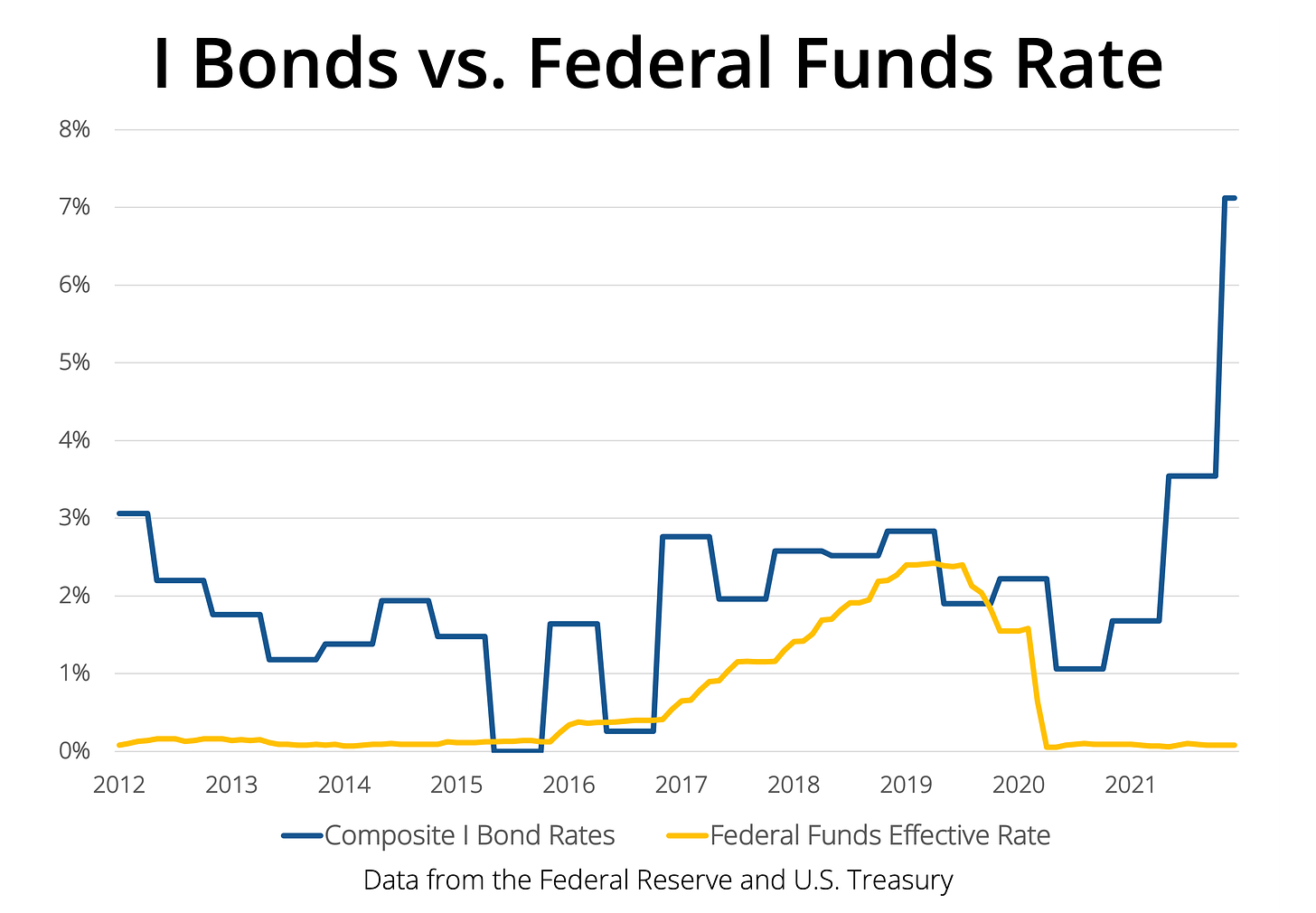

On the surface, I bonds seem like they could be a great investment. They aim to keep up with inflation, plus a little extra, are considered safer than investing in the stock market, and are currently paying much more than savings accounts and other cash-equivalent accounts (and much more than other types of U.S. government bonds). Despite these qualities, they’ve only recently gained relevance and popularity. The chart below illustrates how they weren’t very popular until recently.

I bonds were quietly flying under the radar until recently. Why weren’t savers ten, five, or even two years ago clamoring for I bonds? The answer lies in the chart below.

This chart shows composite I bond rates (which is the fixed interest rate and inflation rate combined) over the past ten years, compared to the federal funds rate. In 2012 I bonds were briefly paying about 3% more than the federal funds rate, but that spread shrunk until disappearing completely in 2015. For several months over the last ten years, the federal funds rate has actually exceeded the composite rate of I bonds. The return of I bonds rose with the federal funds rate through 2019, both dropped at the start of the pandemic, and since then the funds rate has remained near 0% while the composite rate of I bonds has skyrocketed.

What does this all mean? The federal funds rate is a decent proxy for how much consumers can earn on cash-equivalent accounts, such as high-yield savings accounts. Over the last ten years, consumers haven’t been able to earn significantly more by investing in I bonds than they would be able to earn by putting cash in a savings account. Savings accounts are much more convenient, with no depository limits, so consumers had no reason to choose I bonds over cash-equivalent accounts (until 2021).

Why are I bonds popular now?

Last year inflation rose, and the interest paid on I bonds rose with it. The federal funds rate did not go up; this rate usually rises with inflation, but the target rate is set by the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve has not yet withdrawn support from the economy (more on that later), so there is a huge spread right now between the interest you can earn on a savings account and the amount you can earn by investing in I bonds.

In case all of that went over your head, in the past you could choose between earning 2% investing in I bonds or 1.5% investing in your savings accounts.† Most consumers chose savings accounts because they are more convenient; you can put in as much as you want (though it all may not be FDIC insured), there are no early withdrawal penalties, and your cash is liquid and can be used for emergencies. Plus, I bonds were, and still are, a sort of niche investment that the general public isn’t aware of. Nobody invested in I bonds because there was no real reason to.

Now, I bonds are paying over 7% (and that’s just the inflation rate; the fixed rate is currently at 0%)††, and the federal funds rate (the proxy for the amount you can earn on cash-equivalent accounts) remains near 0%. Does this mean you should put as much money as you can in I bonds?

Drawbacks of I bonds

There are several drawbacks to investing in I bonds you should consider before you buy as much as you can. The biggest drawback is that I bonds are illiquid. They aren’t redeemable until you’ve held them for 12 months, and if you redeem them before the five-year mark you will lose three months of interest as a penalty. I bonds are also non-marketable, which means you can not sell them on a secondary market and you can only buy them from the Treasury.

This makes I bonds a poor choice for an emergency fund. An emergency fund needs to be readily accessible when you need it. If you had an emergency within 12 months of moving your emergency fund to I bonds, you’d be out of luck.

The limits on I bond contributions are fairly low. To invest the full $15,000 annually, you would have to give the government an interest-free loan of $5,000 and then use your tax refund to buy paper bonds. That is not convenient or ideal. If you are saving for a house or a larger purchase, you may not be able to invest enough in I bonds to meet your goal. The smaller limits mean the difference in interest paid isn’t as significant. If someone is choosing between investing $10,000 in I bonds at 7% or in a savings account earning 0.5%, that’s a spread of 6.5%, which is large, but amounts to just $650 annually on a $10,000 investment.

This is not to mention the fluctuating inflation rate on I bonds. That 7% rate is good for six months and six months only; afterwards, the rate on I bonds could still be high or it might be more comparable to other cash-equivalent accounts.

Are I bonds a good investment?

We are living in unique times where the interest rate on I bonds is significantly higher than you can earn on almost any cash-equivalent investment or bond without taking a significant amount of risk. If you have short- to medium-term savings goals that are between one to five years in the future, it could be worth considering investing in I bonds. There is no guarantee that future rates will remain near where they are today, but they can help you keep up with inflation at a time when cash-equivalent accounts are unable to do so.

The spread between the rate paid on I bonds and the rate you can earn in a savings account won’t exist forever. The Federal Reserve recently announced they expect to raise interest rates three times this year, to a target of 0.75% to 1.00% (I wrote more about what that means here: “The Federal Reserve Is Raising Interest Rates. Should You Be Worried?”). It remains to be seen whether the federal funds rate will rise to meet inflation, if inflation will moderate and move closer to the federal funds rate, or a combination of both, but they can not exist out of equilibrium long-term. The Federal Reserve has already signaled they are willing to raise rates to combat inflation. It is likely that I bonds won’t appear as attractive as they are now over the next several years.

Investing in I bonds won’t make you rich, but we are in unique times where they could make your dollars stretch a little bit further than those of your peers. In inflationary times, they can be an option worth considering for short- to medium-term savings goals. We like to say that Financial Mutants are able to make their dollars work 5% to 10% harder than the general population, and for some, investing in I bonds could make up part of that 5% to 10%.

† Refer to the chart above. Rates varied, and at some points there was an attractive spread between I bonds and the federal funds rate, but nothing like we’re seeing now.

†† In the chart above I used the current composite rate, which means it is the rate someone would earn if they invested in I bonds at the time. If they had invested in I bonds earlier, they might be earning a higher or lower rate, since the fixed rate is good until maturity (30 years). Fixed rates on I bonds peaked in 2000 at 3.6%. I like to think there’s at least one person out there that bought I bonds in 2000, is still holding them, and is currently earning 10.72% (the current inflation rate + their 30-year fixed rate) on government bonds in 2022.