Stagflation is when a country experiences a stagnant economy and high inflation, typically accompanied by high unemployment. The word “stagflation” can summon unpleasant feelings in anyone who knows what it is or has lived through a period of stagflation. It is one of the most painful economic periods for consumers to live through, and one of the most confusing for central bankers and politicians. Stagflation defies traditional economic theory; stagnant economic growth, high unemployment, and rising prices should theoretically never occur simultaneously. If the economy is doing poorly and more Americans are unemployed, prices should not be rapidly rising. To learn more about how stagflation exists, and why it happens, we need to know the history of stagflation.

A brief history of stagflation

The term “stagflation” was first used in the United Kingdom in the 1960s and later migrated to the U.S. in the 1970s following the oil crisis. In the United States, the Federal Reserve was not especially successful fighting stagflation (to be fair to the Fed, it is challenging to fight something you’ve never seen before, and several factors were out of their control). The 1973 oil embargo, when OPEC imposed an embargo against the U.S. and oil prices quadrupled, certainly didn’t help. The U.S. was very dependent on foreign oil and acutely vulnerable to an embargo. The price of oil skyrocketing helped inflate prices across other sectors of the economy.

President Nixon’s actions that were aimed to combat inflation instead are believed to have made the problem worse. He instituted a wage and price freeze for 90 days (during the 1972 presidential campaign), imposed a 10% tariff on imports, and removed the United States from the gold standard. The oil crisis and Nixon certainly contributed to stagflation, but the Federal Reserve played a large role as well. Their “stop and go” monetary policy, raising and lowering interest rates in quick succession, confused consumers and businesses and did little to mitigate inflation or unemployment.

Why does stagflation happen?

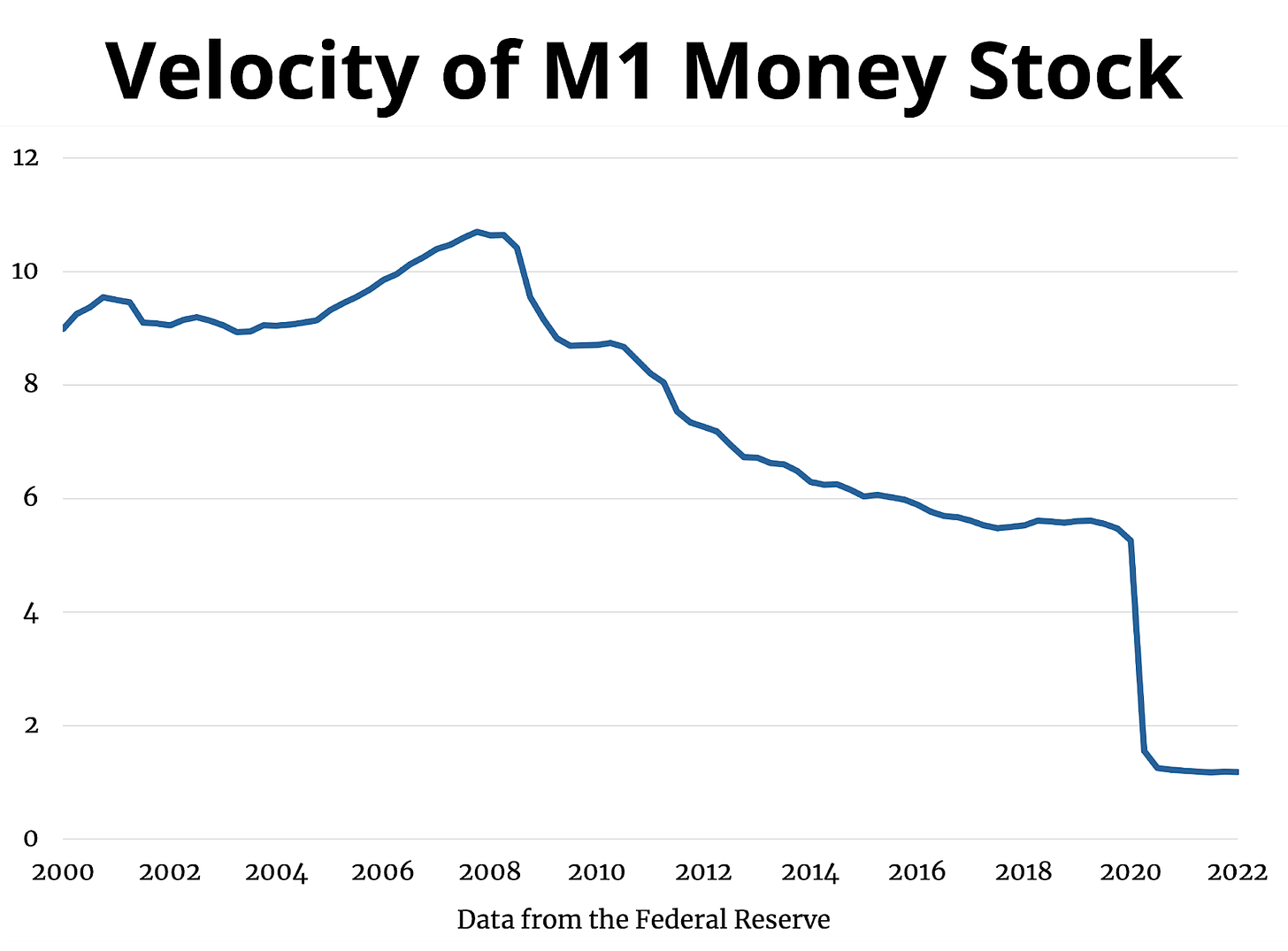

Stagflation generally shouldn’t happen in a free market economy, which means it may occur when outside factors influence the economy unnaturally. Too much fiscal stimulus has the potential to cause stagflation. When production in an economy slows, the velocity of money slows and the economy contracts. In 2020, we saw a major slowdown in the economy, due to businesses shutting down, and the velocity of money also slowed to a halt (seriously, check out the chart below). In response, the federal government issued several rounds of fiscal stimulus in an attempt to stave off a recession. The money supply increased 23% year-over-year from 2019 to 2020, almost double the prior peak money supply growth rate. The Federal Reserve balance sheet has more than doubled, from just under $4 trillion to over $8 trillion in assets, since the start of the pandemic.

More money was being poured into the economy than ever before, yet something strange was happening: consumers weren’t spending it. The personal savings rate in the U.S. reached nearly 35% at its peak, in April of 2020, and didn’t start coming down until April of 2021. Americans were at home, not going to restaurants, not traveling, and not spending money. They were able to save more than ever before, which is great! When we were able to start spending money again, we did (and more than the economy could support).

The Consumer Price Index increased 2.6% from March 2020 to March 2021, which came in a bit higher than expected. Inflation at that time was written off as a sign of a “strong economic recovery,” and “many economists, as well as policymakers at the Federal Reserve, expect[ed] the increase to be temporary.” Data for April was projected to be higher than March, and it was, at 4.2%, and then inflation numbers were expected to decrease as the worst months of the shutdown fell out of data comparisons. “Transitory” became the buzzword of the Federal Reserve.

Not everyone believed inflation was temporary. On the day March inflation data came out, at 2.6%, the following was written in an article for USC Economics Review:

“…the inverse relationship between increasing money supply growth and declining money velocity is a large red flag for possible inflationary issues.”

The signs were there; a huge amount of money was being injected into the economy, but it wasn’t being spent. Eventually that money was going to work its way through the economy, and it did, kickstarting inflation in April of 2021.

As soon as the personal savings rate started decreasing, inflation started increasing. This was not a coincidence; Americans were trying to spend more money than the economy could support, so prices started going up, much more than expected. Supply chain issues have lasted longer than anyone could have predicted, and are still having a big impact on the economy.

By some measures, we are currently experiencing stagflation. The economy unexpectedly shrank last quarter, while inflation has reached 40-year highs month after month. We have a stagnant economy and high inflation, but not high unemployment. The ease at which Americans can find a job helps lessen the pain a bit, but stagflation, if that is what you prefer to call what we are currently experiencing, is making many people miserable.

Why stagflation feels so bad

Inflation alone will not necessarily make Americans miserable. Nobody likes rising prices, but if wages more than kept up with inflation, it wouldn’t be as big of a concern. The latest data showed that real average weekly earnings decreased 3.4% from April of 2021 to April of 2022 based on the change in CPI. However, CPI is not always an accurate measure of inflation. If you bought a house, or a car, or renewed your lease, your real wages likely went down by more than 3.4% over the last year. Real individual income decreasing is just one sign of a slowing economy; usually this coincides with a decrease in sales and production and an increase in unemployment.

How the Federal Reserve can fight stagflation

The Federal Reserve has tools to fight inflation and tools to fight a slowing economy, but not tried-and-true tools to fight both at the same time. Right now, they are planning to deploy tools to fight inflation. This includes increasing interest rates and decreasing monetary support of the economy. Plans could change, and have changed before. It is difficult to know if the Federal Reserve will consider changing course; it is possible that GDP will go down again this quarter, which is the traditional indicator that we are in a recession. If the economy does continue contracting and inflation becomes less of a concern, the Federal Reserve may backtrack and implement looser monetary policies.

Hindsight is 20/20, but the future is never as clear. It’s easy to see now, with the benefit of being able to see everything that’s happened in the economy over the last year, that inflation was likely to be stickier than thought. But few were predicting inflation would stick around as long as it did, and those that were projecting sustained inflation may not have predicted it would be as high as we’re currently experiencing.

The past can help explain the present, but can’t predict the future. We don’t know how the market and economy will react to higher interest rates, how long they’ll be necessary, or what tools the Federal Reserve will deploy. We are committed to providing the tools you need in these unique economic times, and creating content to help explain what is going on in the economy and in your personal finances. In this episode, we discuss how to protect your money during inflationary periods.

Often the best course of action you can take is to stay the course. Don’t let fear dictate your financial decisions, but do assess your plan, and if things have materially changed, adjustments (not a change) may be appropriate.