Silicon Valley Bank, or SVB, recently collapsed and became the second-largest bank in the U.S. to fail (and the largest since 2008). Fears are running rampant; the market is extremely fearful of contagion spreading and runs on the bank happening at other institutions. Signature Bank collapsed shortly after SVB to become the third-largest bank to fail in U.S. history. What happened at Silicon Valley Bank and should you be concerned about your bank collapsing?

What happened at Silicon Valley Bank?

Banks are for-profit institutions. While many customers don’t pay for banking services directly, banks still make money by using customer deposits to loan out or invest in generally low-risk investments. Banks are required to keep only a fraction of deposits on-hand for withdrawal at any given time. This means that if everyone shows up and demands their money back from the bank at the same time, not everyone will be made whole (by the bank; the FDIC covers deposits, up to certain limits, in such situations).

Normally, this isn’t a problem because people trust that banks are going to have their money when they need it, so they don’t all show up at the bank at the same time demanding their money. As long as everyone trusts the bank, everything usually works out fine. Problems occur when trust in the bank is shaken – and that is what happened with Silicon Valley Bank.

A significant portion of customer deposits at SVB were invested in U.S. government bonds. Government bonds are considered a safer investment, but they can go down in value. If you bought a $100 bond from the government last year paying 1%, it will be worth less if someone can now buy a $100 bond paying 4%. This isn’t a problem if you can hold your bond to maturity: you’ll get your $100 back from the government, plus the 1% per year. It’s a problem when you are forced to sell your bonds on the open market because customers want their money back.

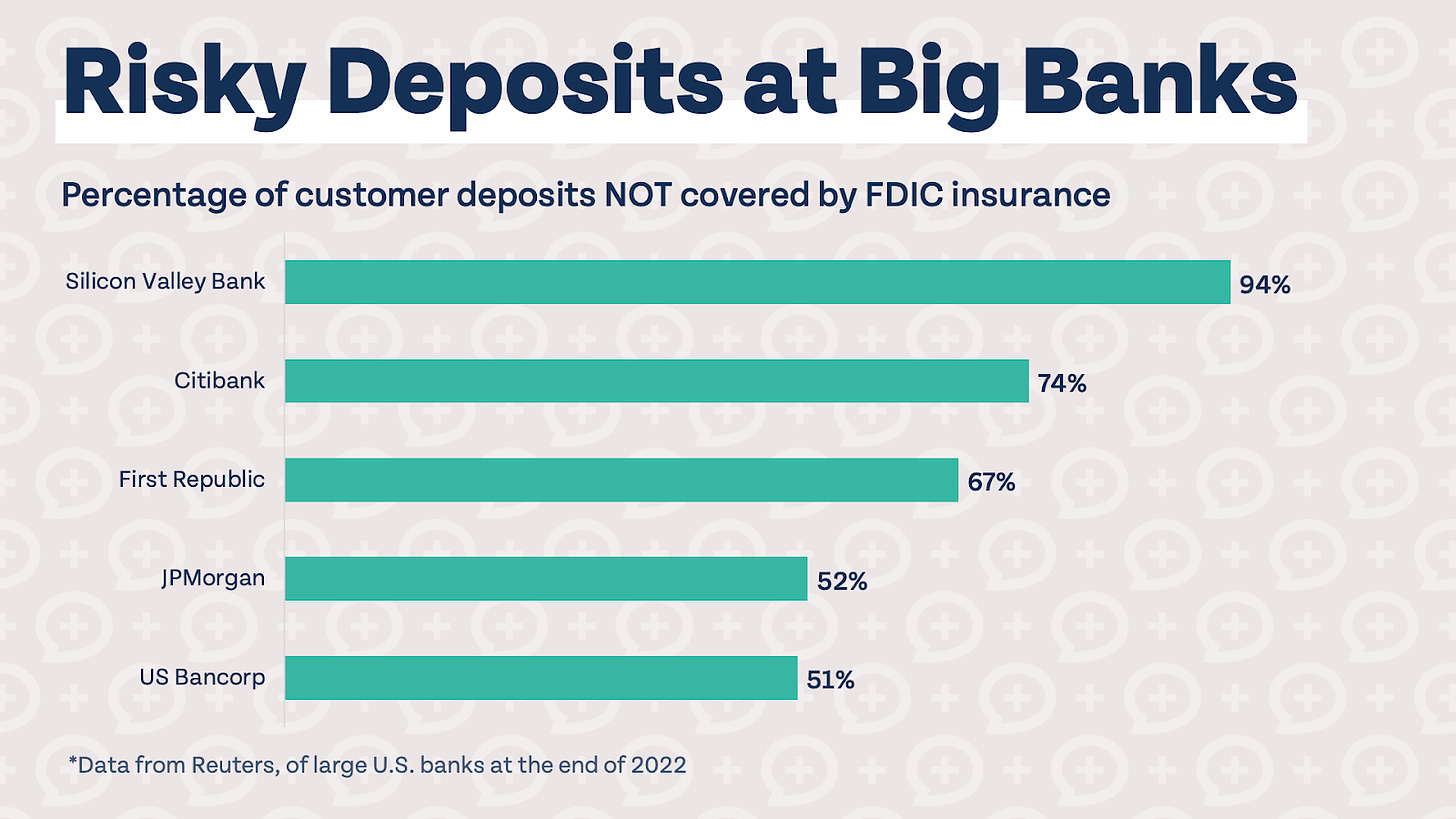

The situation at SVB is a bit more complicated, but you get the picture. Deposits were tied up in bonds that had gone down in value, customers became nervous and started a run on the bank, then the government stepped in. The situation at SVB was unique because the vast majority of customer deposits were uninsured – more so than any other large bank in the U.S.

The amount of deposits not covered by the FDIC could have made customers a little more nervous they wouldn’t get their money back, and added a little extra fuel to the fire. Ultimately, the Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC announced that all customer deposits, even amounts over $250k, would be backstopped by the federal government.

What if my bank collapses?

Bank failure is not a common occurrence, but it isn’t rare, either. Two large banks recently collapsing (and some others having financial troubles) does make customers more on edge about their own bank, and even if a bank is not in any bad financial trouble, bank runs could still cause a bank to collapse.

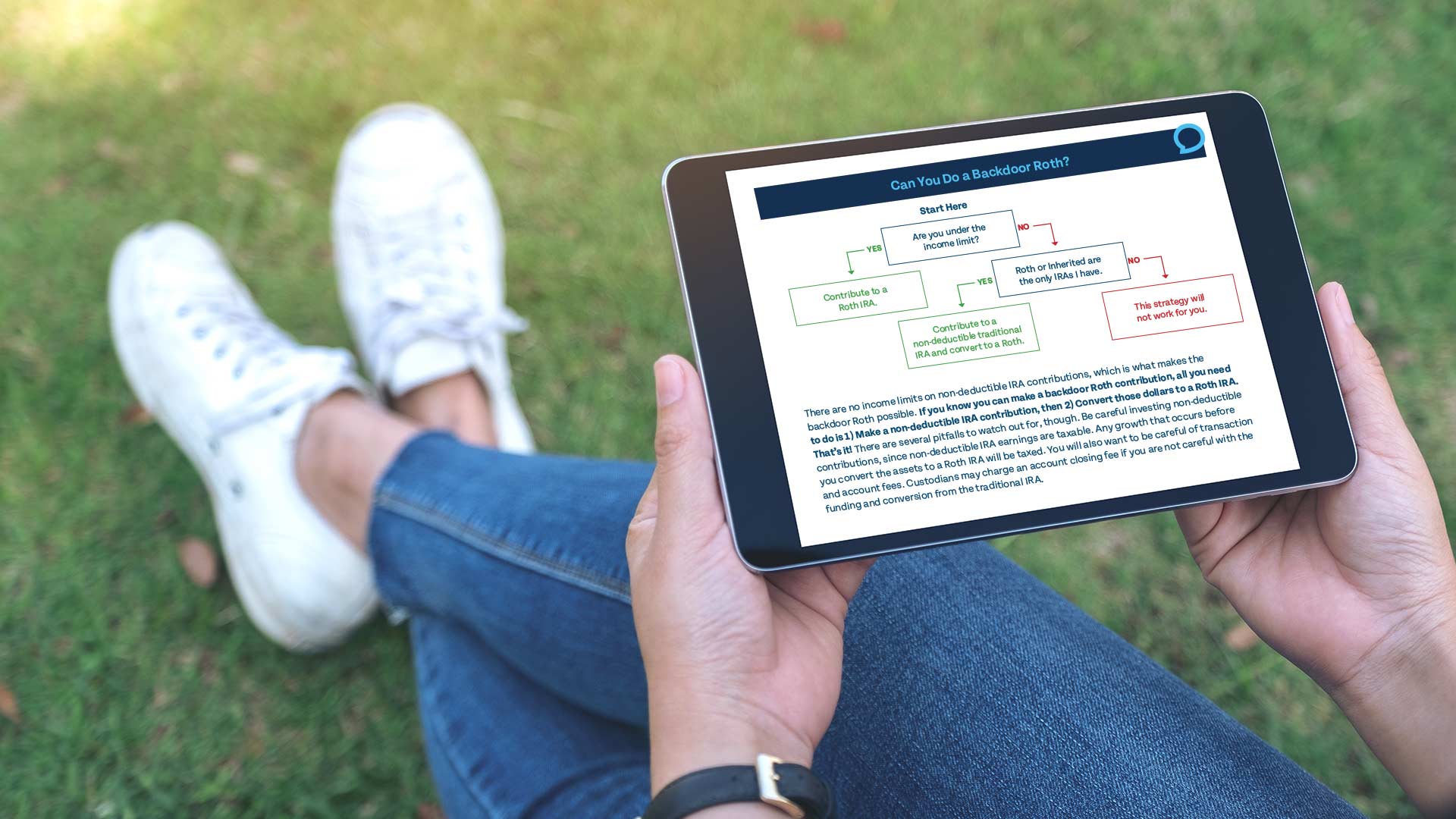

Most Americans have less than $250,000 in cash (in fact, most have less than $1,000 in cash) and are fully covered under the FDIC. If you have more than $250,000 in cash, there are ways you can increase your FDIC coverage. One is adding a joint owner to your account, which increases your coverage to $500,000. Different institutions have separate coverage limits, so opening an account at another bank can increase your coverage (credit unions also have separate coverage under the NCUIF). You could also open an account with a different registration type at the same bank, like a trust, that qualifies for separate coverage.

What about my investment accounts?

Most don’t have to worry about exceeding the FDIC coverage limits, but many more Americans have a significant amount of investments. How is that covered, or is it covered at all?

SEC rules prevent brokerage firms from using your assets for their own business. Custodians keep assets segregated, which means even if your brokerage went bankrupt, your investments should be returned to you or transferred to another provider. Consider investing with a brokerage that has been around a long time and is transparent about how they handle customer assets. Fidelity, Vanguard, and Charles Schwab all fit the bill.

It is possible that not all brokerage firms operate within the bounds of the law, and customer assets could be missing if a brokerage firm went bankrupt. If this were to happen, assets would be covered under the Securities Investor Protection Corporation, or SIPC. It covers up to $500,000 in securities, including money market funds, and up to $250,000 of cash held in a brokerage account. Many brokerages carry coverage in excess of SIPC coverage, which kicks in if SIPC coverage were ever exhausted. If you are concerned, check with your broker to see exactly what coverage your accounts are eligible for.

It’s important to remember that while security holdings are protected under the SIPC, the value of those securities is not. It is always possible for investments to go down in value and lose money. If you have other concerns or questions about the recent collapse of SVB, make sure you check out our recent Q&A or watch it on YouTube below.

We put a lot of trust and faith in banks and investment firms to be good stewards of our hard-earned resources. It is frightening whenever something happens that causes us to question that trust and faith. We have experienced large banking collapses before, and are grateful for the safety nets put in place to ensure your assets are protected. The events surrounding SVB should serve as a spot check for your financial well-being. If you had a good plan before SVB collapsed and were banking at reputable institutions, that plan should continue to serve you well. Don’t get caught up in a cycle of irrational fear and make a poor decision that could negatively impact your financial future.